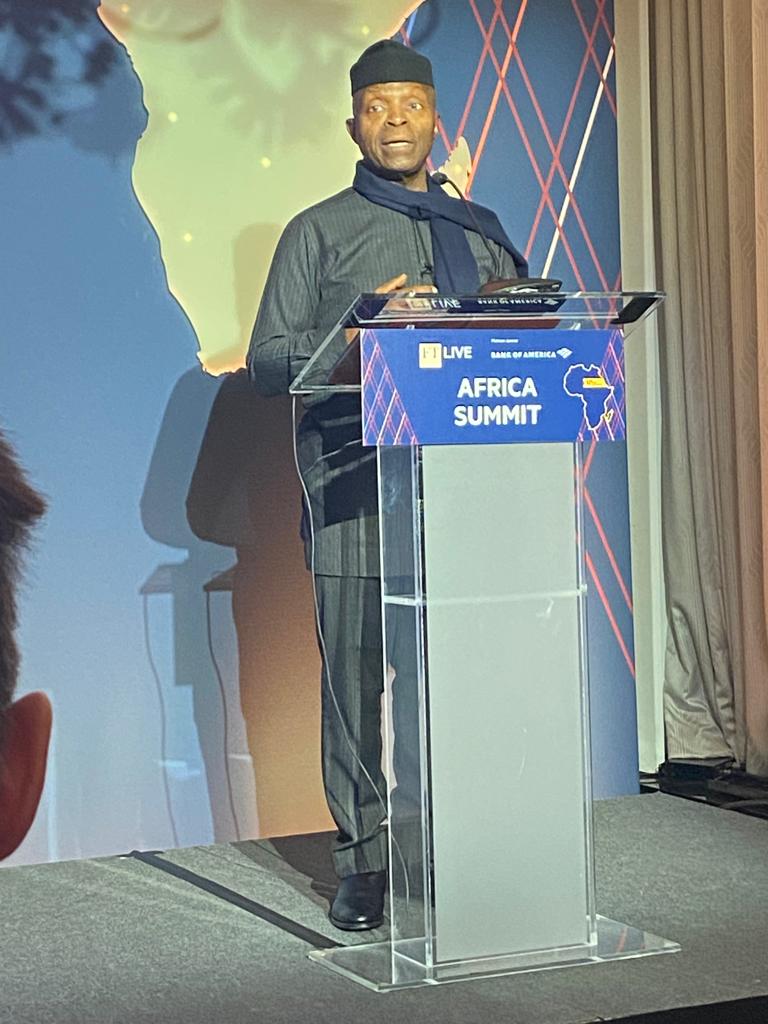

10th Anniversary Of Financial Times Africa Summit In London

REMARKS BY HIS EXCELLENCY, PROF. YEMI OSINBAJO, SAN, GCON, IMMEDIATE PAST VICE PRESIDENT OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA AT THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF FINANCIAL TIMES AFRICA SUMMIT THEMED: “HOW AFRICA IS NAVIGATING THE ENERGY TRANSITION,” IN LONDON ON THE 17TH OF OCTOBER, 2023

PROTOCOLS

How Africa is Navigating the Energy Transition.

Answer 3 questions:

Did Africa succeed in getting its points across at COP27?

Will gas become a transition fuel, and will finance and insurance be available?

Which economies can use the transition to their advantage, developing hydrogen industries and effective carbon sink and carbon credit strategies?

In navigating the transition perhaps, we should bear in mind that for Africa there are two, not one, existential challenge. The first is climate change, which despite being the least emitters we are the most vulnerable to its ravages. The second is survival for 1.4billion people, 32% of whom live in extreme poverty – A situation substantially caused by lack of energy access.

So, going into Cop 27 and in the preceding years, by and large, the conversations around what a just transition would mean for Africa, have revolved around how to fund adaptation and mitigation, and loss and damage. Consequently, one of the ambitions going into Cop 27 included Raising Adaptation Finance. Relative to mitigation, adaptation finance is largely underfunded.

Some progress was achieved at COP 26, where the final text of the Glasgow Pact urged developed country Parties to at least double their collective provision of climate finance for adaptation to developing country Parties from 2019 level by 2025. The doubling of adaptation finance would amount to an additional $40 billion.

The annual adaptation costs for developing countries will be between $140billion – $300billion by 2030 and $280billion – $500billion by 2050, UNEP’s Adaptation Gap Report.

The big prize at COP 27 was the surprise formal recognition of and the decision to establish the loss and damage fund. This was Africa’s No. 1 shared priority at COP 27.

The problem with these funding arrangements of course is that they are not economic or commercial propositions. They are more in the nature of philanthropy from the goodness of the hearts of wealthier nations, many of whom are pressed with their own economic challenges, opposition parties yelling country first, and other nationalist and isolationist rhetoric. The easy answer is to deprioritize these commitments.

Not surprisingly, the wealthier nations have a rather poor track record of honouring these obligations. We are of course yet to see how the loss and damage fund will be funded.

But going into COP 28, Africa proposes a transformational shift.

At the Africa Climate Summit in September, the Nairobi Declaration embraced a Climate Positive Growth Plan as the economic and development paradigm for Africa.

What does the Climate Positive Growth Plan entail?

First, we recognize that, historically, economic growth goes hand in hand with emissions growth. This is the pathway that the wealthier countries have traversed, which brought us to this imminent apocalypse. If Africa were to grow along the same carbon-intensive trajectory to middle to high-income status, we would add 12 gigatons of emissions annually up to 2050, and that would mean that global net zero ambitions would be impossible to attain.

Africa’s answer then is to be the solution to the world attaining its net zero ambitions while we attain our urgent economic and developmental objectives. How?

It is by pursuing a pathway of economic growth that does not grow emissions, does not even keep emissions constant, but actively addresses the reduction of emissions and the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere by (1) greening global manufacturing and supply chains and (2) removing carbon from the air – the two things the world needs to attain net zero by 2050.

Africa is uniquely positioned to do this as it has the world’s largest untapped renewable energy potential, the youngest and fastest growing workforce, and massive natural resources including critical mineral assets.

For example, if Africa processed the bauxite it mines (25% of global bauxite production) to aluminium with renewable energy before exporting it, we could save 335 million tonnes of CO2e per year (1% of global emissions!), create 280,000 jobs, and generate $37billion of additional revenue for the continent.

In fact, by aggressively deploying its renewable energy resources, Africa can provide energy to all Africans, 600 million of whom currently do not have access to energy and 150million of whom have unreliable access to energy, at a 30% lower cost and with over 90% lower emissions per kWh, compared to the current stated policy.

Africa’s renewable energy is not only abundant but also has very low seasonality, which makes it possible to reliably provide renewable baseload, to power continuous industrial production. Solar PV in Nigeria and in Kenya vastly outperforms Europe’s industry CENTRE and even Europe’s top PV spot. The same battery-supported PV system in Nigeria will enable a baseload that is 8 times as large as Germany.

Some of the work that GEAPP is doing, especially the launch of the Battery Energy Storage Systems in (BESS) in Malawi (best example), Vietnam, India, Indonesia, and South Africa shows the possibilities of distributable renewable energy in DRC (Nuru) DREAM (Ethiopia), Haiti, India showing how community by community, solar grids can solve power problems for domestic and industrial uses.

Battery Precursors

A Bloomberg study done for AfDB in 2021 on the manufacture of battery precursors found that manufacturing battery precursors in DRC (DRC has plenty of Lithium and Cobalt) is 3 times cheaper than US, EU and China, and manufacturing in DRC would expand value chain opportunities to other African countries. For example, they would need manganese from Zambia, Tanzania, Gabon, South Africa to contribute to its capacity to produce these battery precursors.

No export of raw ore

Several African countries now have restrictions on raw exports of critical minerals. Zimbabwe, Africa’s largest lithium reserves, Namibia, DRC, Nigeria, and now over 42% of African countries, excluding North Africa, have those restrictions. So, mining Companies are now establishing processing plants.

Delta in Skills

These are great opportunities, but making up the delta in skills and capacity is important. Laws must insist on robust training programs for local engineers and others required to operate the plants.

Use of renewable energy to mine and process, so Africa can become the green industrial hub of the world – the cost-effective green factory for the world is a great prospect, but it would require at least the following: First, a fair and equitable access to global markets for its climate-smart products.

Second is the right level and type of investment – of the right tenor and with the cost-of-capital that makes these investments viable.

Which economies can use the transition to their advantage, developing hydrogen industries and effective carbon sink and carbon credit strategies?

The past five years have seen tremendous growth in the blue and green hydrogen industry, with many green hydrogen projects in Africa reaching the Final investment decision (FID) – Angola, Namibia, South Africa are already invested.

For African countries with hydrogen ambitions to maximize the opportunity some critical issues must addressed. The first is avoiding the type of competition for export markets that may lead to a race to the bottom for prices. So, developing a unified African strategy for green hydrogen development – like the Africa Green Hydrogen Alliance, in May 2022.

The second is looking at the opportunities for value addition, and manufacture of green steel, green cement, and solar panels using green hydrogen.

As for the issue of countries developing their carbon credit strategies, I will just highlight two matters of importance.

Carbon Markets

The African Carbon Markets Initiative was launched at last year’s COP27. It is an initiative led by GEAPP, with SE4All, UNECA and UN Global Champions, since then has done extensive work on carbon market activation plans for a pipeline of 20 countries. It has created an Advanced Market Signals platform and has seen quite a few commitments. So, the work of ACMI is crucial in developing the capacity of African nations to benefit maximally from their carbon assets.

The second issue is the question over what some have described as the new rush by corporations from wealthy countries to acquire and manage millions of acres of forests in African countries and capture carbon credits by managing and conserving those forests to sell carbon credits to governments and corporations.

Some concerns expressed include the prospect of communities losing control of their forests.

The revenue may not be worth the deal and may not get to relevant governments or the forest communities. The process may also lead to bogus credits. The rules for these trades under Article 6, especially in avoided deforestation, will take place at COP 28.

Will gas become a transition fuel, and will finance and insurance be available?

For gas-rich and energy-poor countries in Africa, the argument for gas as a transition fuel is simple enough. In the face of energy poverty, with millions lacking access to power, and one in four deaths of women in rural areas caused by pollution from the use of firewood, what sense does it make to leave this versatile, relatively low-carbon fuel in the ground, when it offers today a cheap and available source of electricity for domestic and industrial use and LPG for clean cooking?

However, there is no doubt that financing of gas projects will become increasingly difficult, since African countries have to rely on international finance and DFI funding, all controlled by global north countries, many of whom are banning or supporting bans on foreign-related fossil fuel investments.

Perhaps to a certain extent, the shocks to the supply chain and availability of gas caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine might have tempered this move. Many European countries, in particular in their search for gas, have turned to several of these gas-rich African countries.

As for insurance, there is a great deal of pressure on insurers and reinsurers, especially from climate activists, not to insure fossil fuel projects. Success has been limited though. Insurance appears to largely follow the money, at least for now. Although many large European insurers have shifted away from underwriting coal mining and coal-powered energy plants, most have not shown any real desire to stop underwriting oil and gas projects. Many are saying that gas will still play a pivotal role in our economies for some time to come.

Recently, Chubb announced new underwriting criteria that would require oil and gas extraction projects to reduce their methane emissions. But the question that arises is – for how long can gas survive as a transition fuel?

With every passing day, the pathway out of fossil fuel dependency seems clearer, especially now that renewable energy is consistently cheaper than fossil-fuel-generated energy and (grid level) storage is rapidly improving and becoming cheaper.